The Commissions

Marie Matusz

Vultures

Curated by Roman Kurzmeyer

Opening Friday 18 February 2022, 6 – 8.30 pm

Exhibition 19 – 27 February 2022

Opening hours

Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 6 – 8.30 pm

And by appointment: dertank.hgk@fhnw.ch

Marie Matusz was nominated for the 2020 edition of the Dorothea von Stetten Art Award, alongside Jan Vorisek and Hannah Weinberger. Entitled Until we turn blue, the group of works presented at the Kunstmuseum Bonn on that occasion will now be on view in an expanded form at der TANK in Basel. Very few people were able to visit the Bonn exhibition because it took place during the first phase of the Corona pandemic. It is worth restaging the exhibition in Basel for this reason alone, but it also provides an insight into the artist’s working process: Matusz used the invitation as an opportunity to rework existing pieces and add new ones to the selection exhibited in Bonn. This process-oriented aspect is characteristic of her fluid conception of the artwork and the identity of her work. Marie Matusz’s exhibitions are always precisely choreographed installations that exemplify the artist’s visual thinking and allow the public to share in it. Even though it is visually absent, the exhibition’s thematic core is the human body as a carrier of culture and civilization.

Marie Matusz’s starting point for this group of works was a lithograph by Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) from 1871 that references the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 and was published under the title Épouvantée de l’héritage(Appalled by Her Legacy). The artist copied the lithograph, which features a mourning figure standing cloaked in the middle of a field of corpses, but replaced the year 1871 above her head with a horizontal number 8: the infinity sign. In Bonn, Matusz presented ten identical versions of the revised lithograph together with other works, including two stainless steel mortuary trolleys, in a blue-lit exhibition hall. In her contribution to the Bonn catalogue (2020), Cassidy Toner writes that Marie Matusz’s reference to Daumier and the exhibited sequence of identical images allude “to a cycle that constantly reinvents itself to merely repeat itself within the context of the present.” The method described is a legacy of Appropriation Art, which emerged in the late 1970s and remains highly relevant to the work concept of a younger generation of artists. In the age of the internet, in which copying and repetition are redefining our relationship to reality, the genesis of an artwork is once again receiving more attention as an integral aspect of its identity and is also being addressed by artists in the creative process. The most important elements of Marie Matusz’s installation in Bonn—in addition to the lithographs, this includes the two mortuary trolleys and the blue light that sets the ambience—reappear in the Basel version, albeit in a modified form and in a new choreography, which we will return to later. Formal repetitions (and thus the creation of redundancy) are a hallmark of the way Marie Matusz stages her work. Her focus is always on the exhibition design: the individual works are the result of a process that is at once artistic and curatorial, and deliberately open-ended. The topic of the exhibition is not illustrated in the works; the conceptual depth opens the work up to new forms of expression.

In A Thousand Plateaus (1980), the French writers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari argue that there is no difference “between what a book talks about and how it is made”; this also applies to Marie Matusz’s exhibitions. They each form an “assemblage” (French agencement) and have no object or subject. It took me a long time to realize that in her spatial works the artist is not interested in the wall, the floor, or the ceiling, but in the area, the volume in between. In her exhibitions, for example, her aluminum sculptural works are generally hung in a very visible—and therefore, as I initially thought, too obvious—way on thin steel cables, which are in turn anchored to simple hooks in the ceiling. Her works, however, are not optically stationary objects in space, like the kind that were first discussed in New York in the 1960s, but extremely fragile structures, special fabrics, for example, and non-load-bearing supports, usually made of metal, creating a form of in-between space, revealing absences, visualizing bodies of air, and thematizing an intentionally created emptiness that can stimulate thought. This is rather unusual in contemporary art because visual evidence no longer has an intrinsic value and narration has become more important than the aesthetic argument in recent years. It is also unusual because Matusz works with language, consults texts for the realization of her works, and essentially builds her artistic work on concepts communicated in the titles of her works and the question of their ability to be grasped and represented.

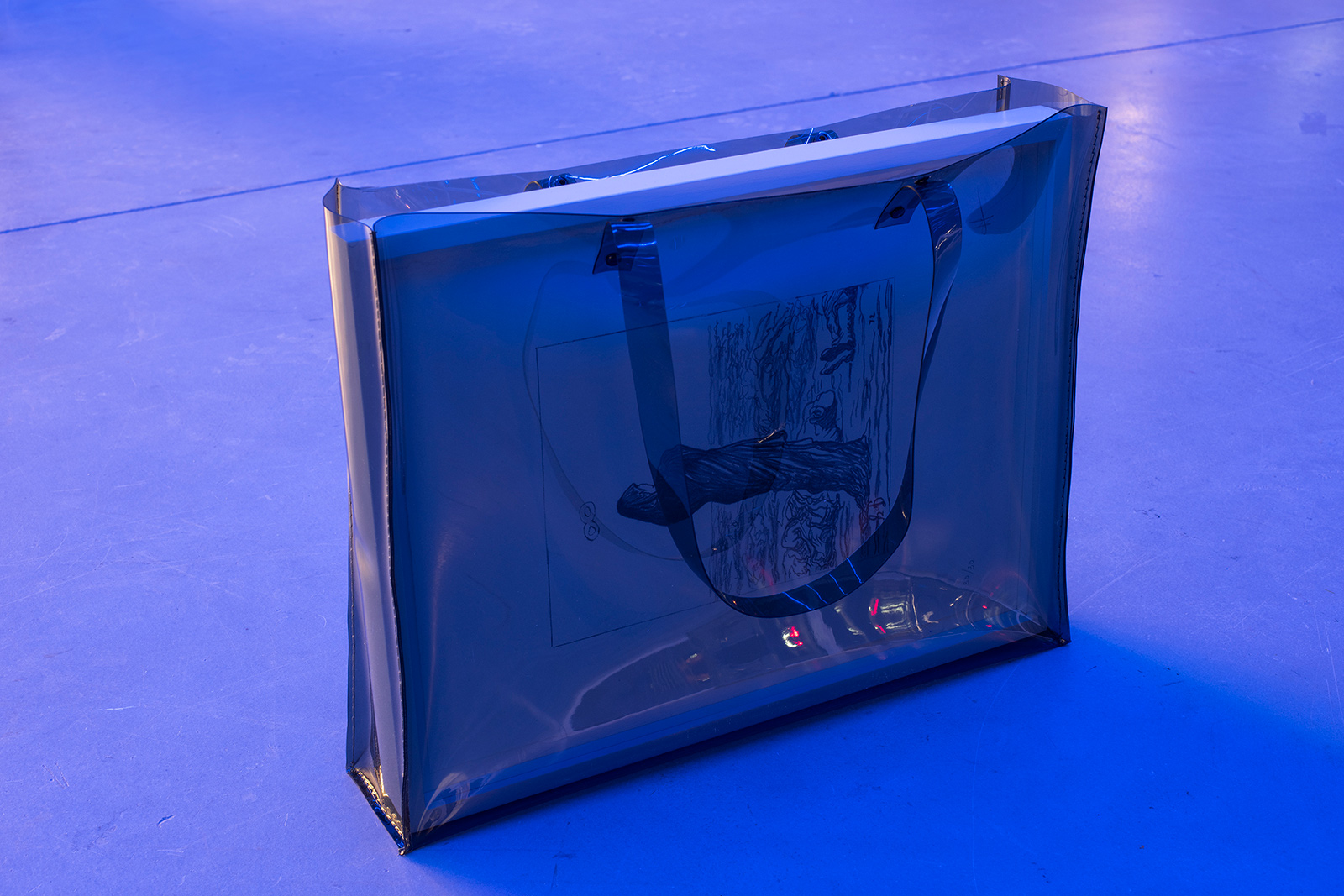

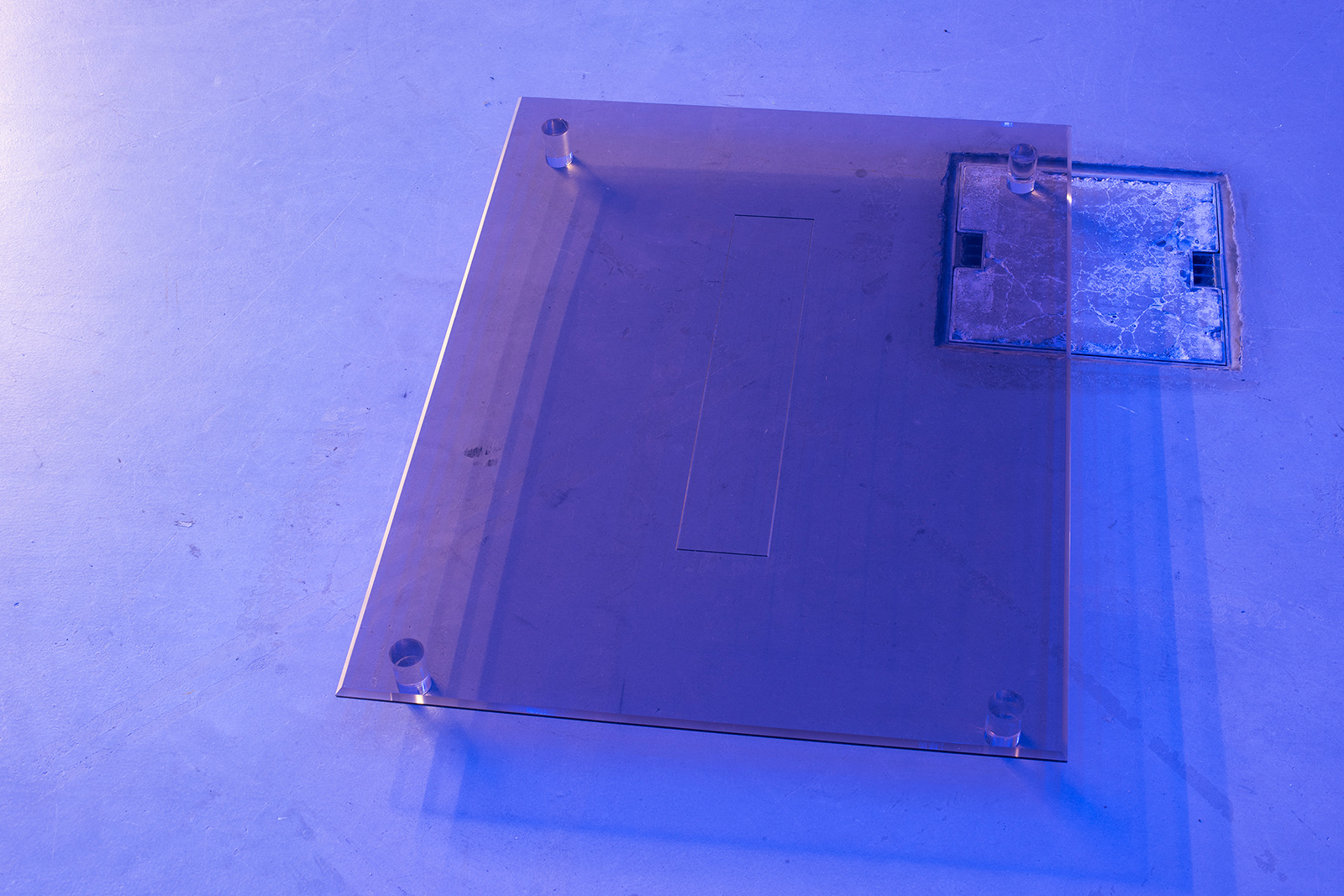

For her exhibition at der TANK, Marie Matusz wrapped the ten framed lithographs in handmade plastic bags, which in turn are individually placed on low pedestals. The pedestals, made of smoke-colored acrylic glass, reflect the blue light like the glass walls of the exhibition space. The stainless steel tables are now like mirrors in the space. The glazed exhibition space, which can be seen from the outside and is only open to the public in the evening, looks like the illuminated display window of a pop-up store, an enormous display case or an archaeological excavation field. Anyone walking around the strictly choreographed exhibition, in which repetition and deviation go hand in hand, will encounter new works that reinforce this principle: sculptures made of beeswax, cement, and ash studded with plastic toy soldiers, and, as an echo of the works inspired by Daumier, ten tear-shaped aluminum objects on the only wall in the exhibition space, each with a female butterfly sitting in their ash-covered interior. Butterflies embody transformation as a cycle. An exhibition as memento mori? Formal and thematic transformation processes are presented in this installation in a visually and intellectually comprehensible and open format for exhibition visitors. Vultures by Marie Matusz is like a labyrinth you can walk through.

Roman Kurzmeyer

The current → Covid-19 protection concept of the FHNW applies.

The Commissions

Marie Matusz

Vultures

Kuratiert von Roman Kurzmeyer

Eröffnung Freitag 18. Februar 2022, 18:00 – 20:30

Ausstellung 19. – 27. Februar 2022

Öffnungszeiten

Freitag, Samstag und Sonntag, 18:00 – 20:30

Und nach Vereinbarung: dertank.hgk@fhnw.ch

Marie Matusz war neben Jan Vorisek und Hannah Weinberger für den Dorothea von Stetten Kunstpreis 2020 nominiert. Die aus diesem Anlass unter dem Titel Until we turn blue im Kunstmuseum Bonn ausgestellte Gruppe von Arbeiten ist nun in einer erweiterten Form im TANK in Basel zu sehen. Die Bonner Ausstellung wurde kaum wahrgenommen, da sie in die erste Phase der Corona-Pandemie fiel. Die Wiederaufführung der Ausstellung in Basel ist alleine schon deshalb angezeigt, gibt aber darüber hinaus einen Einblick in den Arbeitsprozess der Künstlerin: Marie Matusz nahm die Einladung zum Anlass, bestehende Werke umzuarbeiten und die in Bonn ausgestellte Werkgruppe um neue Arbeiten zu ergänzen. Diese prozessuale Dimension ist kennzeichnend für ihren offenen Kunstwerkbegriff und die Identität ihres Werks. Ausstellungen von Matusz sind stets präzise choreografierte Installationen, die ihr visuelles Denken veranschaulichen und das Publikum daran teilhaben lassen. Inhaltlich im Zentrum, obschon visuell abwesend, steht dabei der Körper des Menschen als Kultur- und Zivilisationsträger.

Eine Lithographie von Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) von 1871, mit der er sich auf den deutsch-französischen Krieg von 1870/1871 bezieht, und die er unter dem Titel Épouvantée de l’héritage (Erschüttert über die Erbschaft) publizierte, bildete für Marie Matusz den Ausgangspunkt für die Entwicklung ihrer Werkgruppe. Sie kopierte die Lithographie, ersetzte aber die Jahreszahl 1871 über dem Kopf der Trauernden, die aufrecht stehend und verhüllt inmitten eines Leichenfeldes dargestellt ist, durch die liegende Ziffer 8: das Unendlichkeitszeichen. In Bonn zeigte Matusz diese Neufassung der Lithographie in zehn identischen Ausführungen zusammen mit weiteren Arbeiten, darunter zwei Leichenschauwagen aus Edelstahl, in einem blau beleuchteten Ausstellungssaal. Cassidy Toner schreibt in ihrem Beitrag für den Bonner Katalog (2020), Marie Matusz spiele mit ihrer Bezugnahme auf Daumier und der ausgestellten Sequenz von identischen Bildern «auf einen Zyklus an, der sich fortwährend neu bildet, um sich lediglich in den Verhältnissen der Gegenwart zu wiederholen.» Die beschriebene Methode ist ein Erbe der in den späten 1970er-Jahren entstandenen Appropriation Art, die für den Werkbegriff einer jungen Generation von Kunstschaffenden weiterhin von grosser Aktualität ist. Die Entstehungsgeschichte eines Werkes bekommt im Zeitalter des Internets, in dem Kopie und Wiederholung unser Verhältnis zum Realen neu bestimmen, als identitätsstiftendes Merkmal wieder mehr Aufmerksamkeit und wird von den Künstler*innen im bildnerischen Prozess thematisiert. Die wichtigsten Bausteine der Bonner Installation von Marie Matusz – neben den Lithographien sind dies auch die beiden Leichenschauwagen und das die Atmosphäre bestimmende blaue Licht –, tauchen in veränderter Form in der Basler Fassung wieder auf, allerdings in einer neuen Choreografie, auf die zurückzukommen sein wird. Formale Wiederholungen (und damit die Erzeugung von Redundanz) sind ein Kennzeichen der Werkinszenierungen von Marie Matusz. Ihr Augenmerk liegt dabei stets auf der Ausstellungsgestaltung, die einzelnen Arbeiten sind Ergebnis eines sowohl bildnerischen als auch kuratorischen, bewusst ergebnisoffenen Prozesses. Das Thema der Ausstellung wird nicht bebildert, die gedankliche Vertiefung öffnet die Arbeit für neue Ausdrucksformen.

Was die beiden französischen Schriftsteller Gilles Deleuze und Félix Guattari in Tausend Plateaus (1980) über das Buch sagen, dass es nämlich keinen Unterschied gäbe «zwischen dem, wovon ein Buch handelt, und der Art, in der es gemacht ist», gilt auch für Ausstellungen von Marie Matusz. Sie bilden jeweils ein «Gefüge» (frz. agencement), haben kein Objekt und kein Subjekt. Lange dauerte es, bis ich realisierte, dass sich die Künstlerin in ihren Raumarbeiten weder für die Wand, noch den Boden oder die Decke interessiert, sondern für den Bereich, das Volumen dazwischen. Ihre in Aluminium ausgeführten plastischen Werke etwa hängen in ihren Ausstellungen meist gut sichtbar und deshalb, wie ich zunächst meinte, zu offensichtlich an dünnen Stahlseilen, die ihrerseits an einfachen Haken in der Decke verankert sind. Ihre Werke sind aber keine im Raum optisch stillstehenden Objekte wie sie in den 1960er-Jahren zuerst in New York zur Diskussion gestellt wurden, sondern äusserst fragile Gebilde, spezielle Gewebe beispielsweise und nicht belastbare, meist in Metall ausgeführte Träger, die eine Form von Zwischenraum erzeugen, Abwesenheit zeigen, Luftkörper veranschaulichen und eine absichtlich geschaffene Leere thematisieren, die das Denken stimulieren kann. Das ist in der zeitgenössischen Kunst eher ungewöhnlich, weil visuelle Evidenz keinen Wert an sich mehr darstellt und die Narration in den letzten Jahren wichtiger geworden ist als das ästhetische Argument. Ungewöhnlich auch deshalb, weil Matusz mit Sprache arbeitet, Texte für die Realisierung ihrer Arbeiten beizieht und ihr künstlerisches Schaffen im Kern auf Begriffen, die in den Werktiteln kommuniziert werden, und der Frage nach deren Fassbarkeit und Abbildbarkeit aufbaut.

Die zehn gerahmten Lithographien verpackte Marie Matusz für ihre Ausstellung im TANK in handgefertigte Kunststofftaschen, die wiederum einzeln auf niederen Podesten stehen. Die aus rauchfarbenem Acrylglas gefertigten Sockel spiegeln wie die verglasten Wände des Ausstellungsraums das blaue Licht. Die Edelstahltische stehen nun wie Spiegel im Raum. Der verglaste, von aussen einsehbare Ausstellungsraum, der für das Publikum nur abends offen steht, erscheint wie ein beleuchtetes Schaufenster eines Pop-up-Stores, eine riesige Vitrine oder ein archäologisches Grabungsfeld. Wer sich darin bewegt, trifft in der streng choreografierten Ausstellung, in der Wiederholung und Abweichung Hand in Hand gehen, auch auf neue Arbeiten, die das Prinzip bekräftigen: Skulpturen aus Wachs, Zement und Asche mit eingearbeiteten Spielzeugsoldaten aus Plastik sowie als Echo auf die Arbeiten nach Daumier auf der einzigen Wand im Ausstellungsraum zehn tränenförmige Objekte aus Aluminium, in deren mit Asche bestrichenen Innenraum je ein weiblicher Schmetterling sitzt. Schmetterlinge verkörpern Transformation als Kreislauf. Eine Ausstellung als Memento Mori? Formale und inhaltliche Transformationsprozesse werden in dieser Installation in visuell und gedanklich für die Ausstellungsbesucher*innen nachvollziehbarer und offener Form vorgeführt. Vultures von Marie Matusz ist eine Art begehbares Labyrinth.

Roman Kurzmeyer

Es gilt das aktuelle → Covid-19-Schutzkonzept der FHNW.