The Commissions

Esther Hunziker

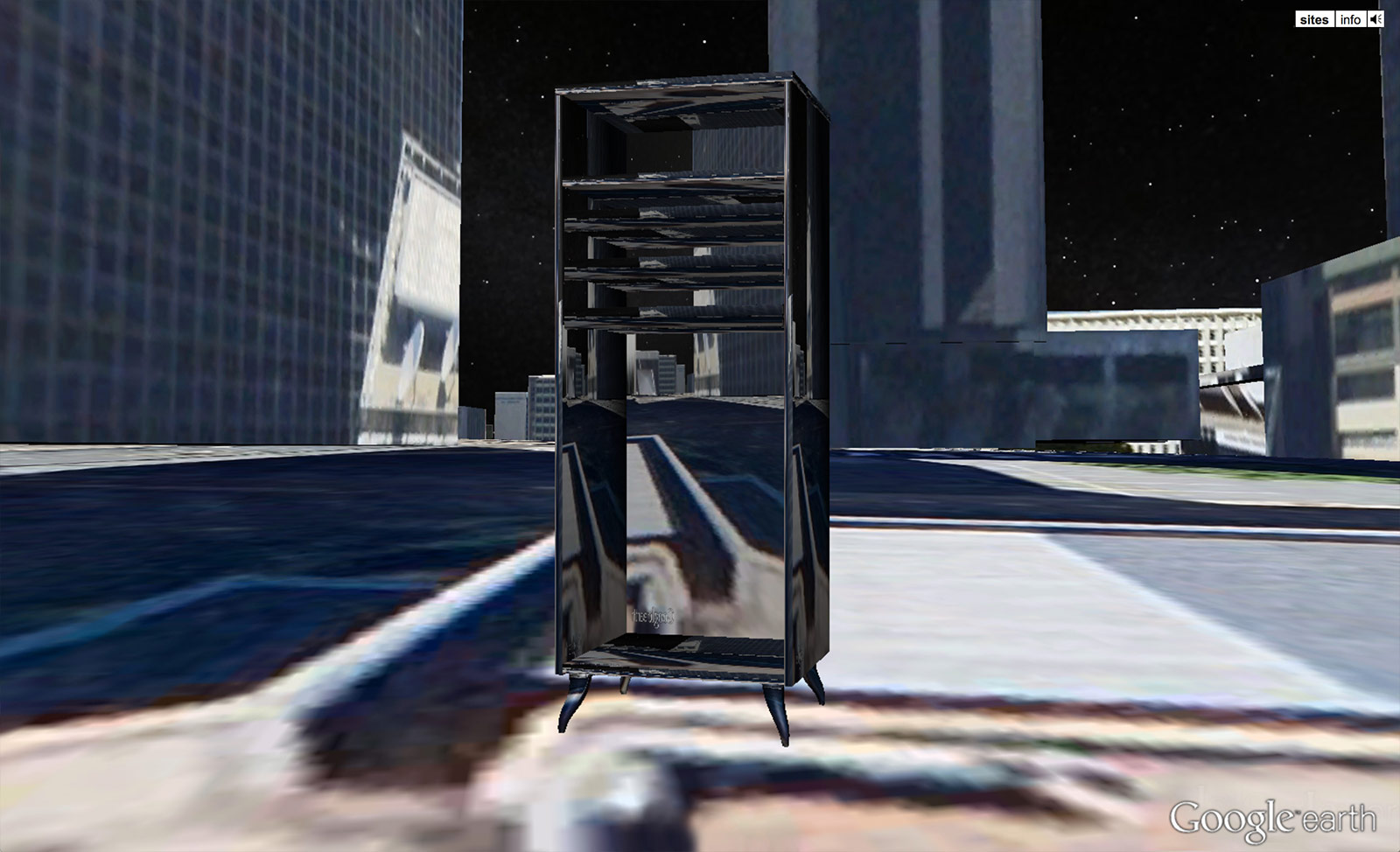

Sites

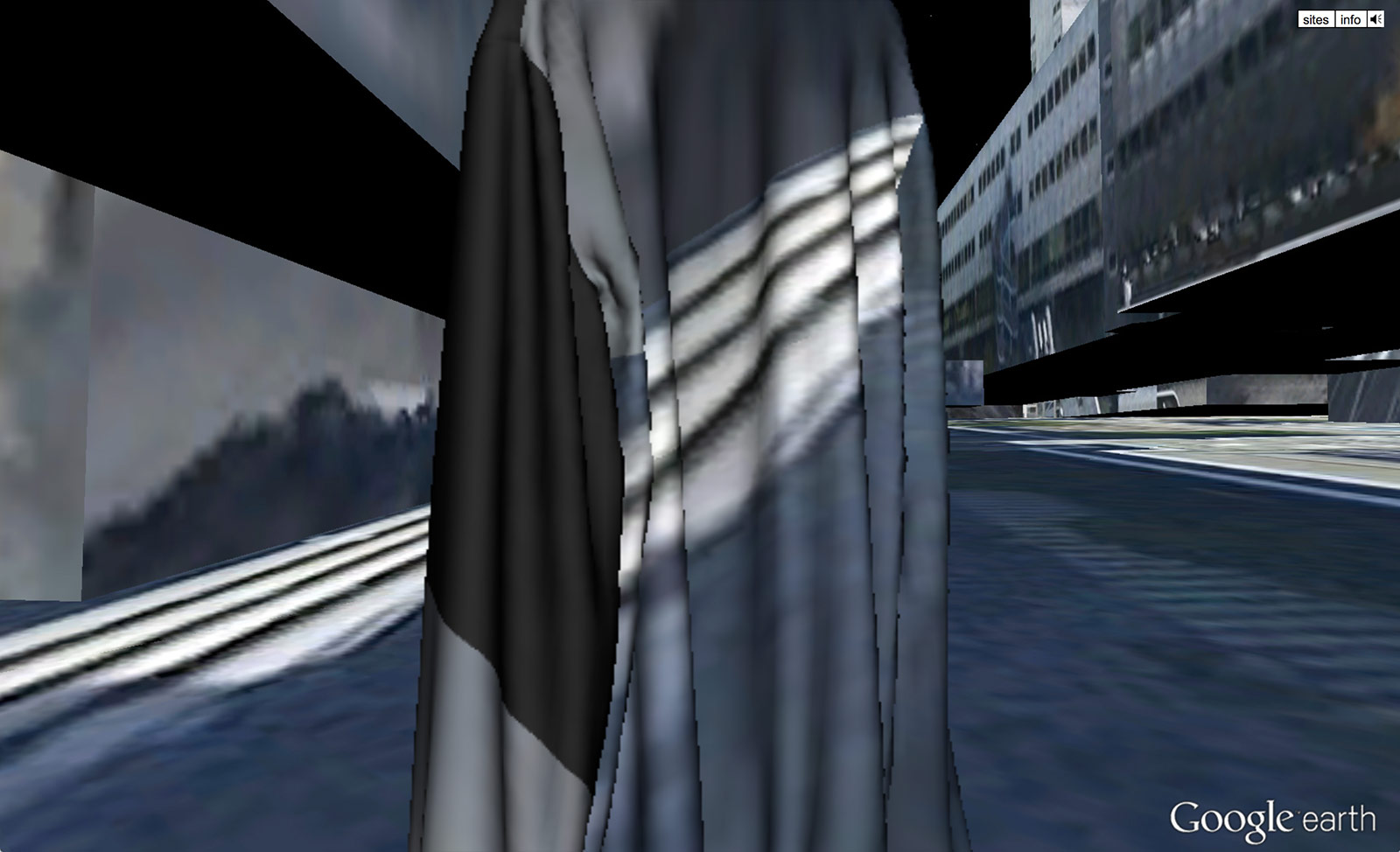

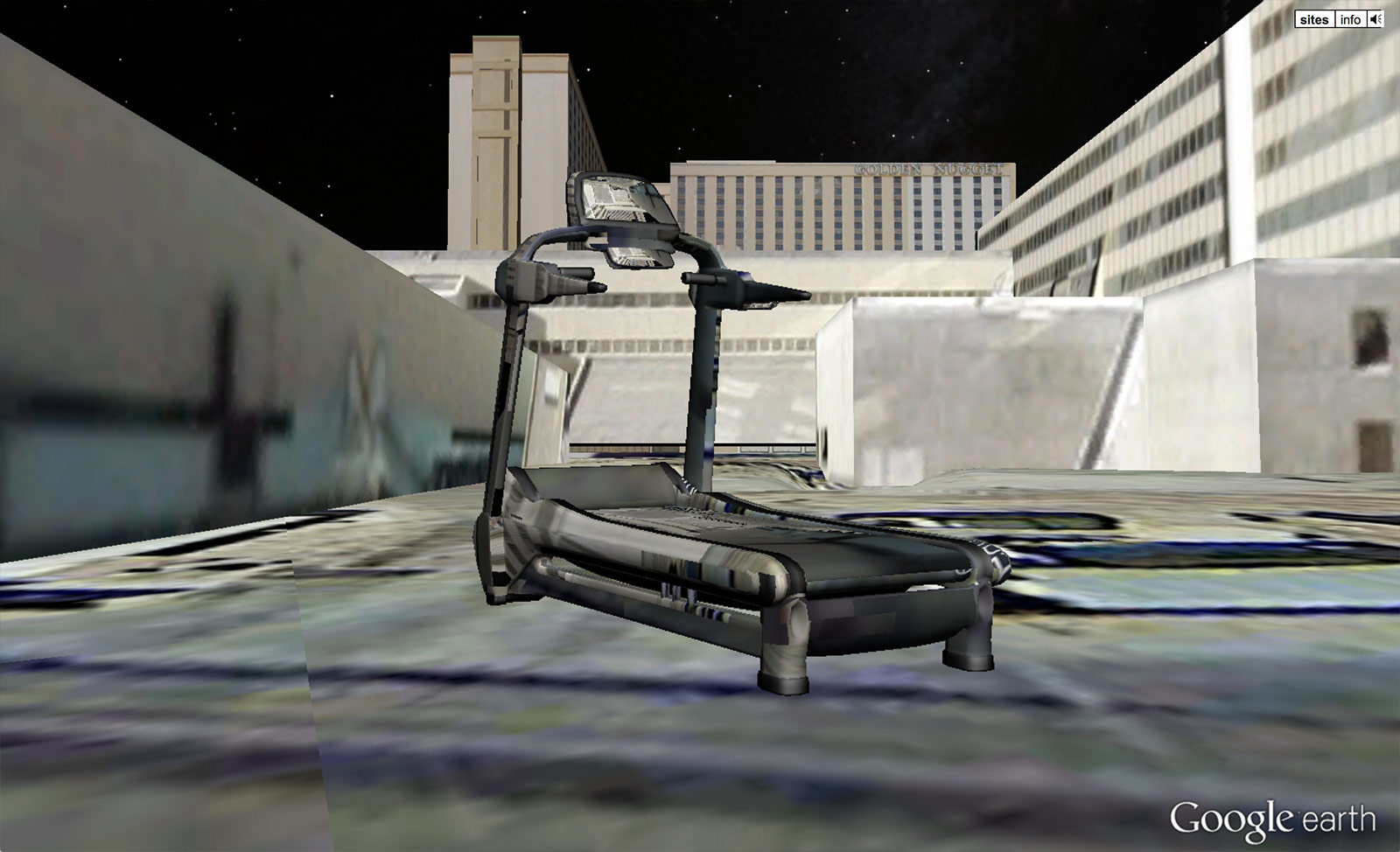

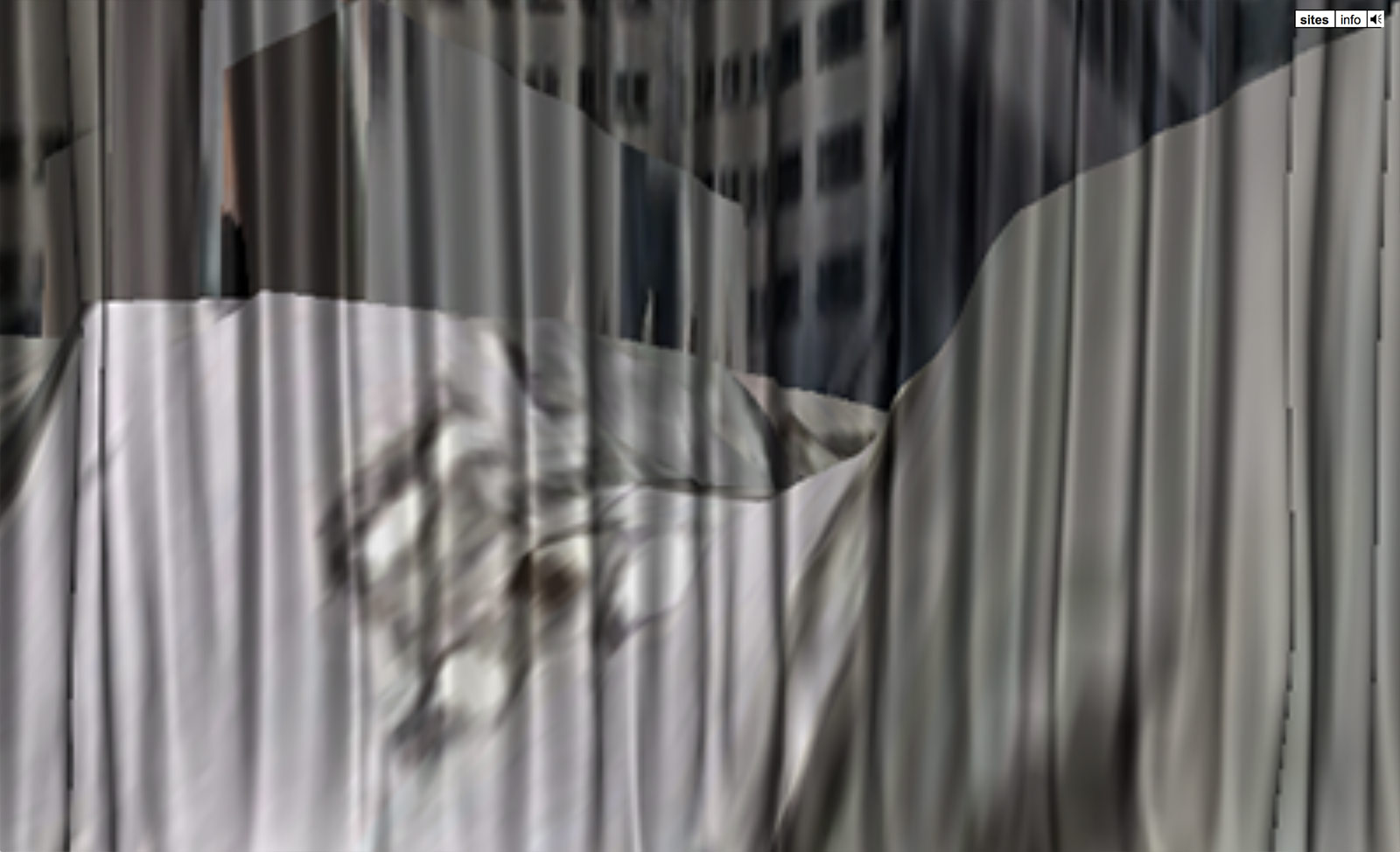

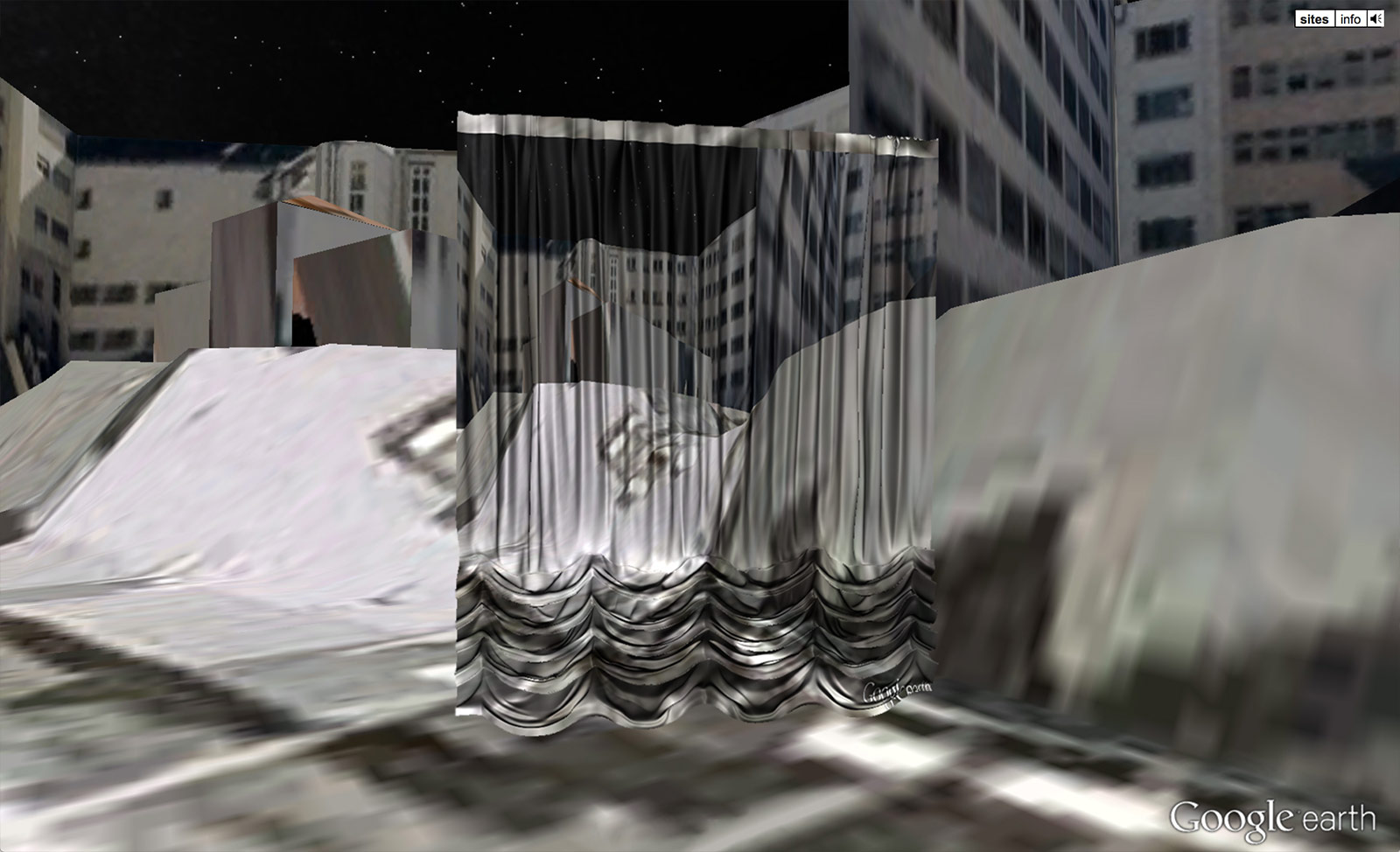

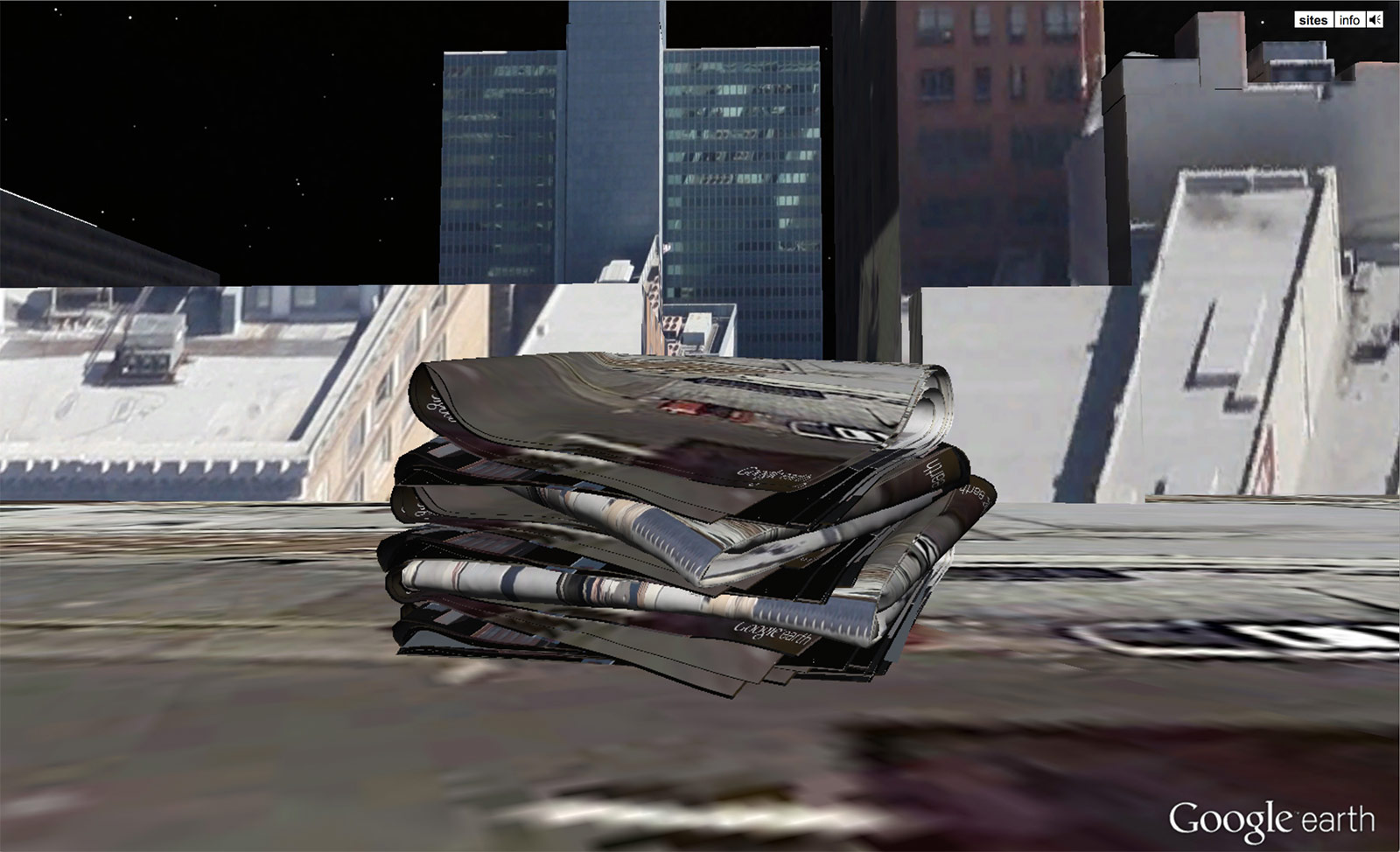

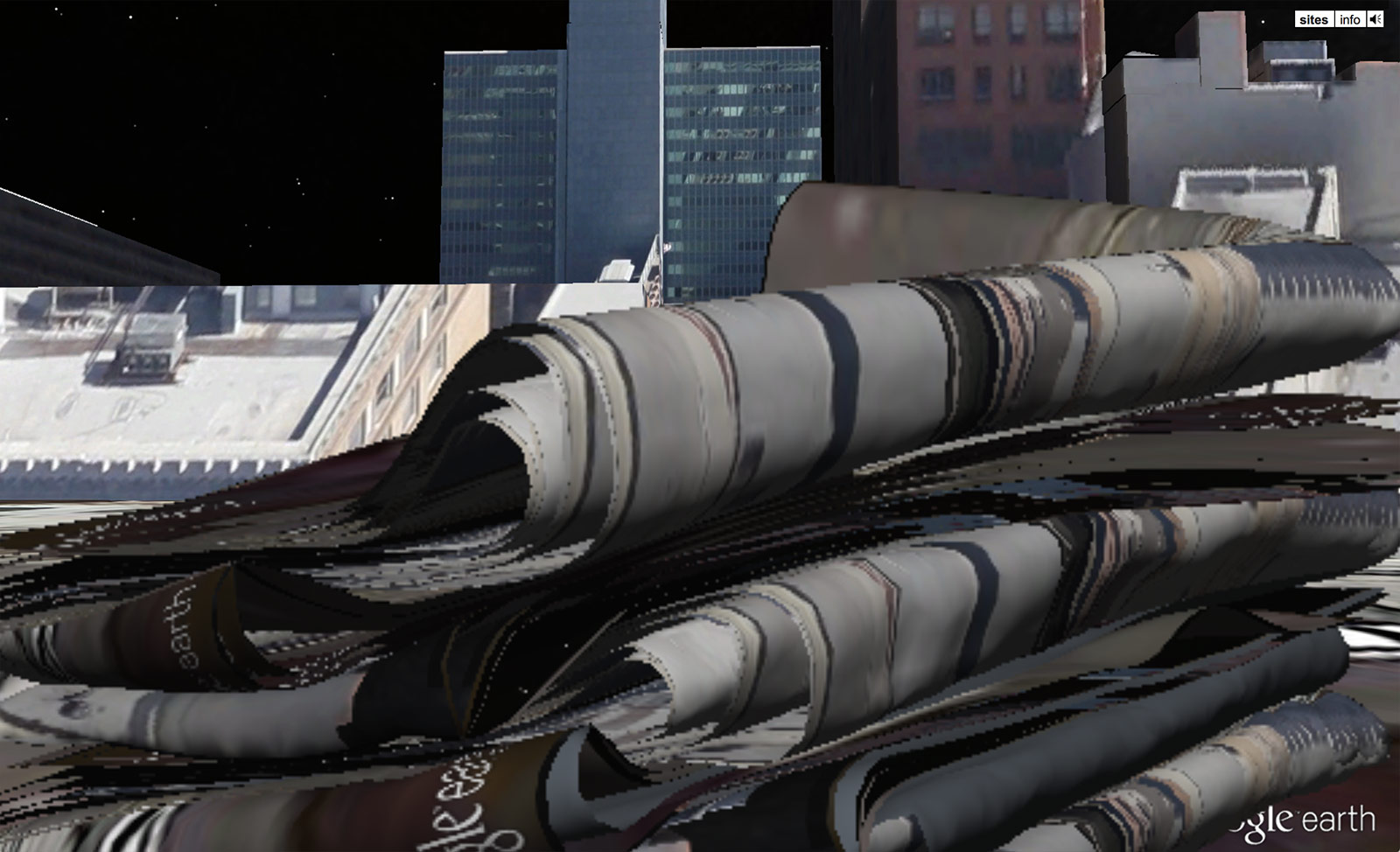

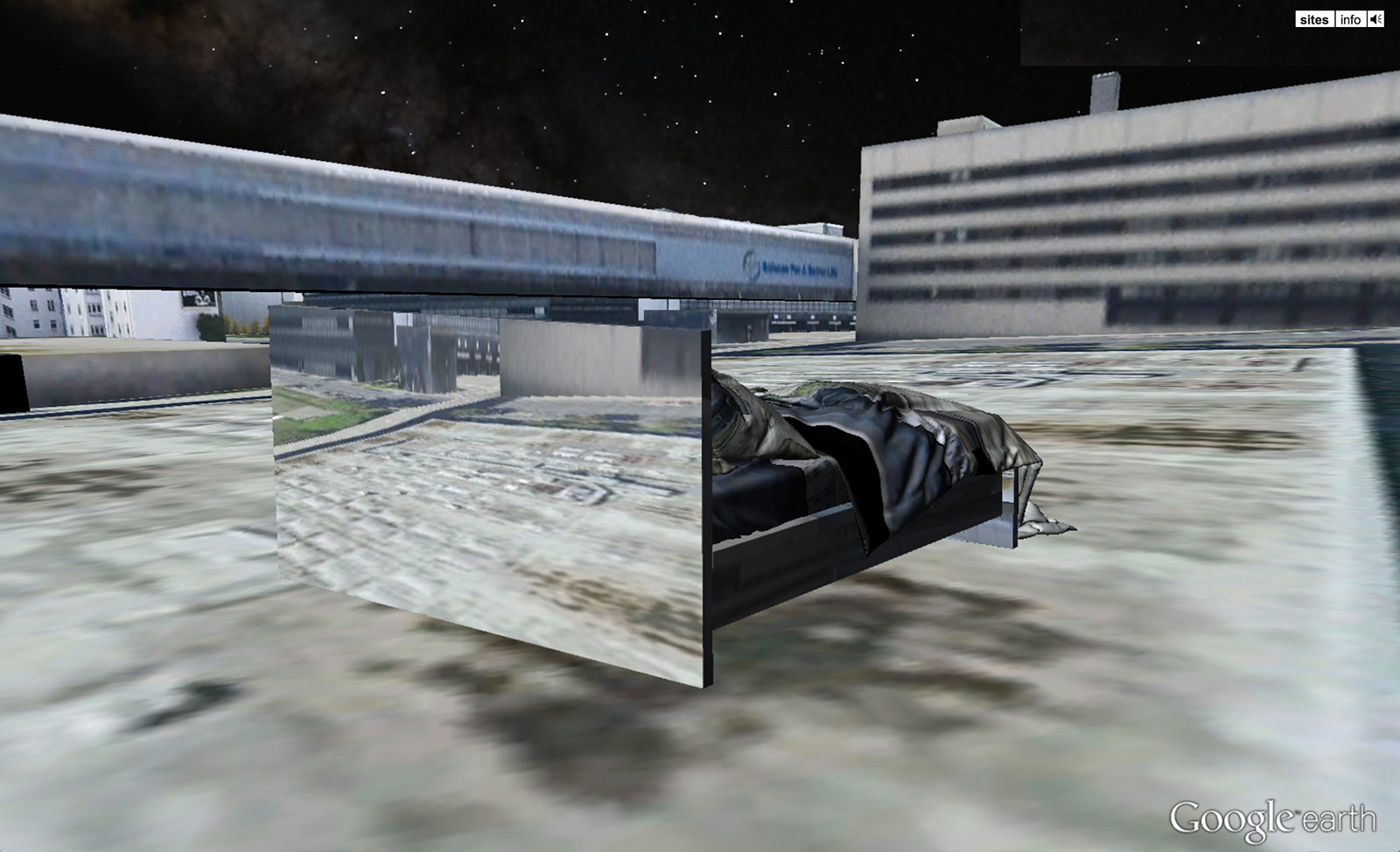

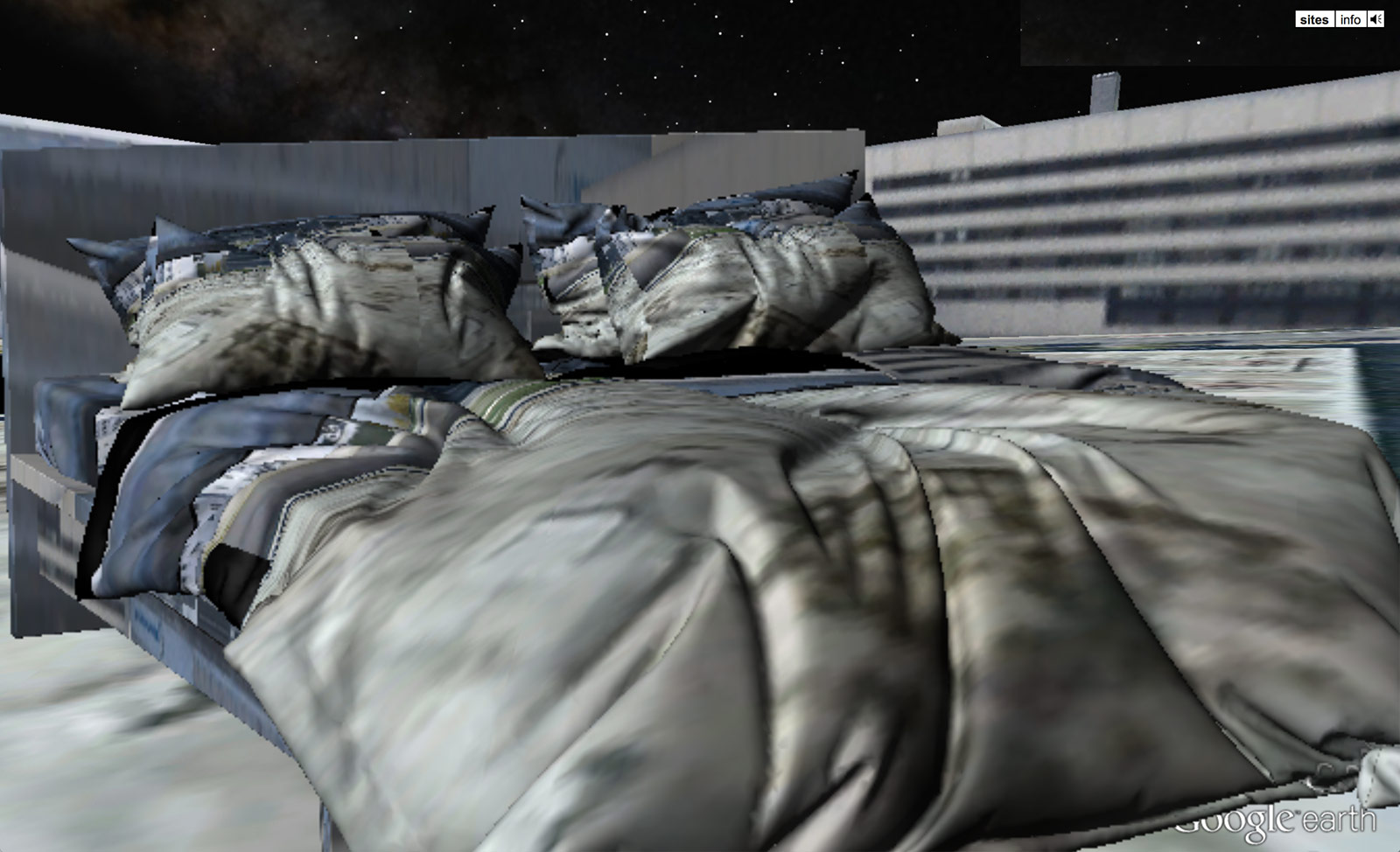

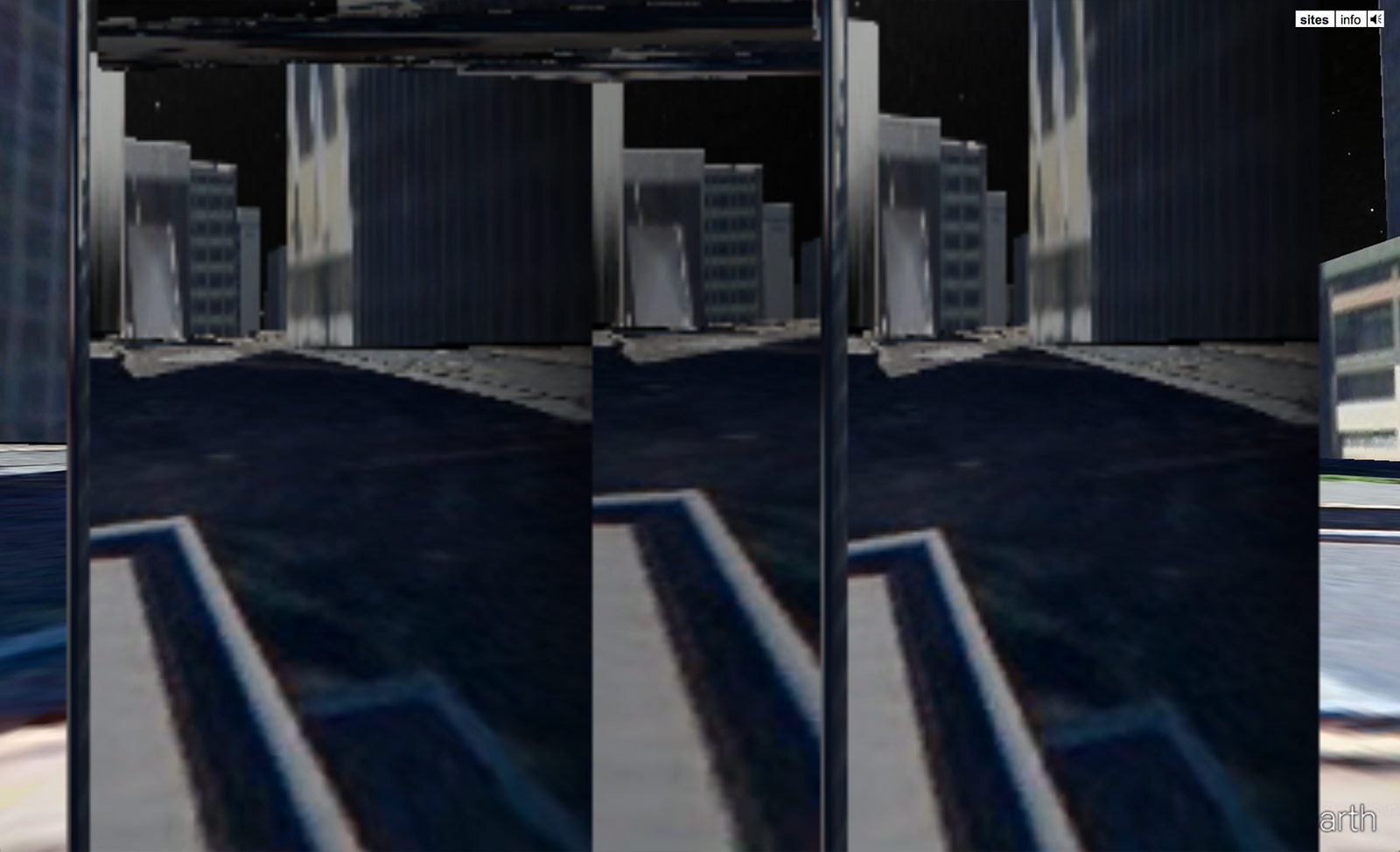

New sites on Google Earth 3D

30 September – 1 November, 2015

Online exhibition on:

dertank.space/online/sites

I have no idea what media art is. I actually do not think that there is a need to say how the image is produced as long as it works. However, the challenge lies in the display, in the fact that traditional ways of showing art do not really know how to deal with the often ugly or too-specific machines on which «media art» needs to be viewed. Yet there has also been the enormous and stubbornly insistent claim, repeated again and again, that traditional exhibition language is not appropriate for it. I do believe in merging though, and this is the reason why—after a team talk—we saw the possibility of having a double-life in exhibition making: a TANK that is a site where projects and works conceived for the Internet are presented, and a TANK that hosts materials and experiments that are physical in a more traditional understanding of the notion.

It is precisely this debate on how to present digitally conceived works that has always interested Esther Hunziker. Her work shows a rare interest in image phenomena that are genuinely part of our Internet culture.

I was talking to a friend the other day. She said she never goes into a shop at all. She buys all she needs online. It surprised her that I never bought a thing online, apart from a few books. She could not believe it. She sent me a few links, thinking that it was perhaps a lack of knowledge that prevented me from it. I started looking through them one night. After-all, why not? At least to see what people like about it so much. It took me some time to understand that the problem is that all those clothes are kind of floating free in a white background. They are sometimes feared by bodies but they do not really have an expression. Moreover, they are completely dispossessed of a reason, a scenery. Somehow, I thought, as a consumer I am dependent on a «disporama», on the invention of a situation that then provokes a reason to dress. But the most beautiful part of this research was, undeniably, the zooming in on the textiles. You could use the function to touch with your eyes the texture of clothes. I thought of Google Earth. I used to «go» to my favorite beach on Google Earth just to see how much it changes over time. Or, better said, I checked to see how regularly they update the picture. I was always annoyed that this particular part of Spanish geography was «portrayed» in winter, and not in summer, when it is really beautiful. Zooming in on the territory, you could, like with the clothes, get closer; you could walk on the sand and see if it were even possible to go into the water. That beach is a complete different thing on Google Earth than it is in my memory, but I can relate to it. With clothes, however, it is different, since the digital memory created by online “touching” may not match the texture of the fabric at home. I thought of Tinder. I also wondered how long it would take not only to see the pictures but to allow the users to come closer, or—similar to how Esther Hunziker operates in her new work—to be able to turn the people around, to simulate some sort of volumetric presence that might help you to make a decision.

All these new functions are tools, and, like every tool, they do not only serve a purpose, they entirely modify the way we see the real. It is also interesting that at the core of the multi-touch screen—and all these functions that play with the idea of our eyes being hands, or forces capable of moving, turning, or affecting objects living in the digital substance—there is an artist: Myron Krueger. He started as early as 1975 to develop his Videoplace, an artificial-reality laboratory that could not only surround users but also respond to them. At the time, the environment was incredibly complex, filming, projecting, and producing a series of sensor-like devices that are at the core of our actual new shopping and coupling experiences.

The work of Esther Hunziker places us exactly at a point where we can reflect upon all these new ways of acting upon the real. Her work makes us attentive to the fact that we are at a strange but interesting point of synthesis between the real-real and the new real. A synthesis that is intended to suppurate old epistemological prejudices against this real we have now been working on for a short century. It is true, for a long time these two trajectories—the real-real and the new real— ran in parallel without crossing paths. But now they have come closer together. We are morphing in ways still undiscovered, ways that offer much more than what they «take» from our former real.

Hunziker’s work points to the fact that by building upon these simple lower-level operations we can learn to perform much more ambitious ones: searching for a new understanding of objects, detecting qualities that the digital does or does not share with the real, better synthesizing the way we produce new settings every day, new circumstances to interact with these millions of digital items. The web is a complete modular system, it is composed of innumerous modules, webs, and multiple elements. We are just at the beginning of learning how this architecture is hosting us and not the other way around.

– Chus Martínez

Ich habe keine Ahnung was Medienkunst ist. Offen gestanden bin ich davon überzeugt, dass es überflüssig ist anzumerken, auf welche Weise ein Bild hergestellt wird, solange es funktioniert. Die Herausforderung jedoch liegt in der Ausstellungsform, im Umstand, dass man gemeinhin nicht so recht weiss, wie man mit den oft so unansehnlichen oder zu speziellen Maschinen und Apparaten umgeht, die man braucht, will man «Medienkunst» zeigen. Die umgekehrte Behauptung ist aber ebenso zutreffend: Mit Nachdruck und irgendwie auch stur hat man stets wiederholt, dass traditionelle Kunstausstellungen für sie nicht geeignet seien. Ich selbst bin von Mischformen überzeugt, und deshalb sind wir – nach einer Diskussion im Team – der Idee eines Doppellebens verfallen, wenn es ums Ausstellungsmachen geht. Der TANK ist eine Website und versammelt Projekte und Arbeiten, die für das Internet konzipiert wurden; Der TANK ist aber auch ein Raum, der Materialien und Experimente beherbergt, die in ihrer physischen Verfasstheit eher den herkömmlichen Vorstellungen entsprechen.

Und genau diese Debatte, wie man digital angelegte Arbeiten präsentieren kann, hat Esther Hunziker immer schon interessiert. Ihre Arbeiten bringen dieses ungewöhnliche Interesse für Bildphänomene, die grundsätzlicher Bestandteil unserer Internetkultur sind, zum Ausdruck.

Vor wenigen Tagen erst unterhielt ich mich mit einer Freundin. Sie erzählte mir, dass sie niemals ein Geschäft betritt. Alles, was sie braucht, kauft sie im Internet. Sie war richtiggehend erstaunt zu erfahren, dass ich niemals irgendetwas online kaufe, abgesehen von ein paar Büchern hin und wieder. Sie schickte mir daraufhin einige Links, vielleicht weil sie dachte, mir fehle der Überblick und deshalb würde ich nichts im Netz einkaufen. Eines Nachts habe ich mir dann die Websites angesehen, zu denen diese Links führten. Warum nicht – schliesslich will man ja wissen, was die Menschen so fasziniert. Ich brauchte eine Weile, ehe ich mich daran gewöhnte, dass alle Kleidungsstücke vor einem weissen Hintergrund in der Luft zu schweben schienen. Manchmal werden sie von Körpern getragen, aber niemals vermitteln sie irgendeinen Ausdruck und obendrein fehlt ihnen jeder «Grund», sie sind nicht in Szene gesetzt. Ich überlegte, wie sehr ich als Konsument von der «Tonbildschau» abhängig war, von der Erfindung einer Situation, die Anlass geben könnte, etwas anzuziehen. Der schönste Teil dieser Erkundungstour aber war fraglos die Möglichkeit, an die Stoffe selbst heranzuzoomen. Man kann die Zoom-Funktion dazu benutzen, mit den Augen die Textur der Kleider zu berühren. Ich dachte an Google Earth. Dort «ging» ich häufig an meinen Lieblingsstrand, um zu sehen, wie er sich im Laufe der Zeit veränderte. Oder besser gesagt: Ich ging immer wieder auf die Website, um zu sehen, wie regelmässig sie dort die Bilder updaten. Als ärgerlich empfand ich immer, dass dieser ganz besondere Ausschnitt der spanischen Geografie nicht im Sommer „portraitiert“ wurde, wo er wunderschön ist, sondern im Winter. Wenn man sich in die Landschaft zoomte, konnte man – ganz ähnlich wie bei den Kleidern – dem Sand immer näher kommen, man konnte ihn buchstäblich betreten und herausfinden, ob es auch möglich wäre bis hinein ins Wasser zu laufen. Auf Google Earth ist dieser Strand etwas völlig anderes als in meiner Erinnerung, aber ich kann zu ihm eine Beziehung aufbauen. Mit Kleidern ist das etwas ganz anderes, da die digitale Erinnerung, die durch das «Berühren» online generiert wird, möglicherweise gar nicht mit der Textur des Stoffes übereinstimmt, sobald ich diesen dann zu Hause vor mir habe. Ich musste an die Dating-App Tinder denken. Ich fragte mich, wie lange es wohl dauern wird, bis man nicht allein Bilder zu sehen bekommt, sondern es den Nutzern möglich sein wird, die Menschen zu drehen – gerade so, wie Esther Hunziker in ihrer neuen Arbeit vorgeht –, eine Art volumetrische Simulation also, die eine Präsenz herzustellen in der Lage wäre, die einem die Entscheidung erleichtert.

Diese neuen Funktionen sind Werkzeuge und wie alle Werkzeuge dienen auch sie nicht bloss einem bestimmten Zweck, sondern modifizieren unsere Wahrnehmung der Wirklichkeit. Interessant ist dabei auch, dass im Zentrum all der Touch-Screens und der Funktionen, die mit der Vorstellung spielen, Augen könnten Hände sein, die Objekte, deren Materialität das Digitale ist, bewegen, durchreissen oder betasten, ein Künstler steht: Myron Krueger. Bereits 1975 hatte dieser seinen Videoplace entwickelt; ein künstliches Realitätslabor, das nicht nur die Nutzer umgab, sondern auch in der Lage war, auf sie zu reagieren. Das Environment war damals ein hochkompliziertes und bestand aus Videokameras, Projektionsflächen und Sensoren, die auch heute im Zentrum der neuen Shopping- und Partnersuch-Erfahrungen stehen.

Esther Hunzikers Arbeit bringt uns geradewegs an jenen Punkt, von dem aus wir über diese neuen Möglichkeiten, auf die Realität einzuwirken, nachdenken können. Ihr Werk macht uns auf den Umstand aufmerksam, dass wir bei einer seltsamen jedoch interessanten Synthese zwischen der wirklichen Wirklichkeit und der neuen Wirklichkeit angelangt sind. Das ist eine Synthese, die sich den schwelenden alten, erkenntnistheoretischen Vorurteilen verdankt, die von der grundsätzlichen Wichtigkeit des Gegensatzes zwischen wirklicher Wirklichkeit und der Realität, die wir nun schon über den Zeitraum unseres kurzen neuen Jahrhunderts bearbeiten, überzeugt ist. Es stimmt, dass diese beiden Bahnen für lange Zeit parallel zueinander verliefen und sich nicht kreuzten, jetzt aber, wo sie sich einander anzunähern beginnen, verwandeln wir uns auf eine Weise, die es nach wie vor zu erkunden gilt und die uns weit mehr zu bieten hat, als sie unserer früheren Wirklichkeit «entnommen» haben wird.

Hunzikers Arbeit beweist, dass wir, aufbauend auf diesen einfachen Operationen einer Eingangsphase, lernen können, anspruchsvollere auszuführen: Die Suche nach einem neuen Verständnis, was ein Objekt ist; auf Qualitäten stossen, die das Digitale mit der Wirklichkeit gemeinsam hat oder auch nicht; eine bessere Vermittlung dafür finden, wie wir tagtäglich neue Konfigurationen und Situationen schaffen, mit Hilfe derer wir mit den Millionen von digitalen Elementen umgehen. Das Internet gehorcht dem Baukastenprinzip und setzt sich aus Bausteinen, Netzen und mannigfaltigen Elementen zusammen. Wir beginnen erst allmählich zu begreifen, in welchem Masse eine solche Architektur uns aufnimmt und einbezieht und nicht umgekehrt.

– Chus Martínez